Lucknow: Where Tehzeeb Still Breathes in Every Lane

Lucknow: Where Tehzeeb Still Breathes in Every Lane

Lucknow: As the winter sun rose softly over the Gomti River on a crisp January morning in 2026, my train rolled into Lucknow Charbagh Railway Station with an unhurried grace. Stepping onto the platform felt less like arriving in a bustling state capital and more like being welcomed into a drawing room where history, hospitality, and culture sit in quiet conversation. The air carried the mingled scents of fresh chai, damp winter earth, and something unmistakably meaty and spiced—an early promise of what lay ahead. Lucknow, the City of Nawabs, did not announce itself loudly. It greeted me with tehzeeb—that ineffable refinement that has defined it for centuries.

Charbagh itself set the mood. The grand red-brick station, with its Indo-Saracenic arches, Mughal domes, and colonial symmetry, stands like a ceremonial gateway. Built during the British era but steeped in local aesthetics, it reflects Lucknow’s essence perfectly: a city where eras overlap without jostling for attention.

Walking Into the Nawabi Past

My first destination was old Lucknow—Aminabad and Chowk—where the city’s heart still beats strongest. Narrow lanes twisted past crumbling havelis, paan shops, perfume sellers, and vendors calling out in melodic Urdu-Hindi. Time here seems to move at its own pace, respectful of memory.

Rising above this maze is the Bara Imambara, an architectural marvel commissioned in 1784 by Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula during a devastating famine. The structure was as much a humanitarian project as a monument, employing thousands and feeding the poor. Standing inside its vast central hall—over 50 metres long with no supporting pillars—I felt dwarfed by human ingenuity. The acoustics are famously uncanny: a whisper at one end travels effortlessly to the other, as though the walls themselves are listening.

Above the hall lies the legendary Bhool Bhulaiya, a labyrinth of corridors designed to confuse invaders. I wandered through its narrow passages, delightfully lost, emerging occasionally onto terraces that offered postcard-perfect views of Lucknow’s skyline. From here, domes and minarets punctuated the horizon, with the majestic Rumi Darwaza framing the city like a royal prologue.

Nearby, the Chhota Imambara, often called the Palace of Lights, shimmered quietly. Built by Nawab Muhammad Ali Shah, its gilded interiors and ornate silver throne room felt like stepping into a jewel box. During Muharram, it glows with chandeliers and lamps, but even in daylight, it radiates a hushed opulence that speaks of a bygone courtly life.

The Rumi Darwaza itself—60 feet of imposing arch inspired by Istanbul’s Sublime Porte—stood timeless, absorbing both history and Instagram selfies with equal patience. Once, Lucknow rivaled Constantinople in cultural ambition, and here, that confidence still lingers.

A City That Feeds the Soul

By midday, Lucknow’s most persuasive argument made itself known: hunger. And in this city, hunger is answered not just with food, but with reverence.

In the crowded lanes of Chowk, I joined the faithful at Tunday Kababi, where the legendary galouti kebabs have been perfected for over a century. Minced so finely they dissolve on the tongue, infused with a secret blend said to include 160 spices, the kebabs were impossibly tender. Paired with flaky sheermal—a saffron-kissed bread—and smoky kakori kebabs, the meal was indulgence elevated to art.

A short walk away, Idris Ki Biryani served a lesson in restraint. The Awadhi biryani arrived in a steaming handi, rice grains long and fragrant, mutton tender enough to fall apart with a sigh. No aggressive spices, no unnecessary garnish—just subtlety, saffron, and rose water working in harmony. Lucknow does not shout with flavour; it persuades gently.

Dessert came in the form of makkhan malai, a winter-only delicacy whipped overnight from milk, cream, and dew. Served at a tiny stall near Akbari Gate, it was as light as a cloud and vanished almost instantly, leaving behind a faint sweetness and a lasting memory. In Lucknow, food is not just eaten—it is savoured, discussed, remembered.

Colonial Echoes and Modern Rhythms

The afternoon led me to Hazratganj, Lucknow’s colonial-era boulevard that has reinvented itself as a chic urban promenade. Tree-lined streets buzzed with life: students debating over coffee, elderly couples strolling hand in hand, shopkeepers displaying exquisite chikankari—the city’s famed hand embroidery.

I stepped into a boutique to examine kurtas so finely stitched they felt like whispers on fabric. Chikankari, introduced in the Mughal era, remains Lucknow’s quiet pride. Watching artisans work, needles moving rhythmically over muslin, felt like witnessing history stitched into the present.

As evening approached, I visited the British Residency, its ivy-clad ruins standing as silent witnesses to the 1857 uprising. Bullet marks scar the walls; shattered halls echo with stories of siege, resistance, and sacrifice. It is a somber place, reminding visitors that Lucknow’s elegance has always coexisted with courage.

Nearby, La Martinière College, built by French adventurer Claude Martin, rose like a European fantasy transplanted into Awadh. Gothic towers, Mughal arches, and lush lawns merged effortlessly—a reminder that Lucknow has always absorbed influences without losing itself.

Culture That Refuses to Fade

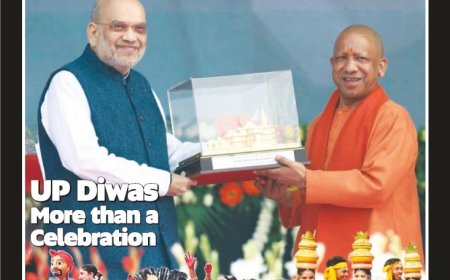

My second day coincided with January’s cultural abundance. UP Diwas celebrations at Rashtra Prerna Sthal transformed the space into a vibrant showcase of Uttar Pradesh’s diversity—folk dances, handicrafts, regional cuisines, and proud storytelling. It felt celebratory yet rooted, like a state introducing itself anew.

Later, at Jashn-e-Adab in Gomti Nagar, Lucknow’s literary soul took centre stage. Poets recited Urdu verses steeped in romance, rebellion, and restraint. Each line was met with appreciative “wah-wah” from the audience. Sitting there, listening to poetry that flowed like the Gomti itself, I felt connected to Mir, Ghalib, and the nawabi mehfils of centuries past.

Modern Lucknow revealed itself fully in Gomti Nagar. The vast Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Memorial Park, with its polished stone, statues, and manicured gardens, glowed under evening lights. Families strolled, children laughed, and the city felt at ease with itself—confident, inclusive, forward-looking.

At the Gomti Riverfront, I chose a slow promenade over a boat ride, watching the river reflect the city’s lights. Nearby, the Nawab Wajid Ali Shah Zoological Garden offered a green escape for wildlife lovers, reinforcing Lucknow’s balance between urban growth and open spaces.

Saying Goodbye, Slowly

No visit ends without one last walk through Aminabad or Chowk. I watched chikankari artisans work, bargained politely—because bargaining here is a conversation, not a confrontation—and bought a final souvenir stitched with patience.

As sunset painted the Gomti in amber and rose, I sat quietly with a final serving of malaiyo, letting the city settle around me. Lucknow had not tried to impress me aggressively. It had simply been itself—graceful, indulgent, thoughtful.

In a fast-changing India, where cities race toward the future, Lucknow moves at its own dignified pace. It reminds you that elegance can endure, that courtesy is a strength, and that history need not be loud to be powerful. If cities were people, Lucknow would be the gracious host who insists you stay longer, eat more, and leave carrying stories—along with, perhaps, a few extra kilos and a permanently softened heart.

What's Your Reaction?